The Conversational Economy — Voice and the New Era of Multi-Modal Computing

Part 3 in a series on the Conversational Economy

“Hey Siri, predict the future of audio interfaces.” If she were smarter, she’d respond that 2017 will be the tipping point — the year we fell headfirst into our always-on, audio-enabled, ambient computing future.

Ambient computing — in the broadest sense — is the promise of computing that is not limited to the 200 times a day you open your phone. It is the promise of ongoing, multi-modal, computing-enhanced interaction with the real world. Increasingly-intelligent listening devices in your home or your ears are a step toward that. Voice is the gateway to ambient computing, and the voice space is incredibly exciting right now. CES feels like the right time to capture a snapshot of the landscape.

Here’s the punch line:

2017 is the year voice becomes a mainstream “operating system,” as we attain “good enough” speech recognition, as voice-enabled hardware gets deployed in volume, and as an ecosystem of companies begins to build in earnest on the big voice platforms (Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft, and in China — Baidu).

People are creating fascinating new hardware computing nodes and voice-native applications. Voice will reduce the effort we expend on data entry, support the disabled, power more predictive applications, and bring new workflows to mobile. These systems are bounded only by their level of intelligence, and by good design’s ability to cover weaknesses in that intelligence.

Challenges abound in enabling technology, design, platform dependence and security.

Voice Arrives with a Bang

Amazon Alexa sneakily grew from novelty to platform, now with 7,000 skills and more than 5 million hardware units sold, and enterprise deployments beginning. The battle for the personal assistant escalated into a multi-front product war amongst giants as Alphabet released the Google Home and the Assistant-centric Pixel phone. Speech recognition has over the last eighteen months become a standard feature on smartphones, wearable devices, and increasingly, home electronics and cars — even your mattress.

Enter AirPods

Americans spent more money last year on wireless headphones than the wired variety. Apple nixed the 35mm headphone port and came out with their truly wireless AirPods (the suspense!). Audio has been a huge part of our lives since the Walkman era — the average American listened to 3.5 hours of music per day in 2015, and the rising generation of millennials listening to even more. We care about our audio equipment’s features, sound, and — since the arrival of Beats on the scene — their style. We use headphones as the first line of defense in controlling our overstimulating environments. I am crestfallen if I forget my headphones. They are my swag badge, the signal in our open floor plan that I’m in flow mode, the tool I use to regulate my mood or focus, the way I take every phone call, the shield against crying babies, and the warning flag to fellow fliers I’m not particularly sociable.

Some use of voice control is already mainstream — in mid-2016, 20% of Android searches were voice-based, and Siri received 2 billion requests per week.

Seemingly incremental improvements can cause a step function change in technology use. It happened in 2008 with the release of the app store, and it’s happening now with audio.

If you have your AirPods in, and your iPhone nearby, you can speak commands into the thin air around you, without touching your phone. You can even skip the annoying “Hey Siri” wake-word with a discrete double-tap of the earbuds. Just this feature will significantly grow my Siri use (from zero today). The AirPods themselves are great hardware. I love them, I use them, they make Siri a new and better experience; there are plenty of glowing reviews already.

Apple's product transition strategy

Unfortunately, your Siri query will often be answered by an unsatisfying on-screen web search result. Siri still lags far behind Google Assistant and Alexa in the all-important areas of reliability, performance, intelligence and integrations — it only works with a few third party apps, notably excluding music services other than Apple’s own.

And yet it is not a huge stretch to go from wearing headphones for several hours a day, to wearing lighter, wireless ones more hours a day, to perhaps even having an earbud in most of our waking hours — especially if they can connect us to applications while allowing us to continue experiencing the rest of the world.

Enabling Tech

On the technology front, last year several companies (including Baidu and Microsoft) declared they’d broken the human barrier of voice recognition, achieving at-par accuracy with humans through deep learning approaches. Impressive progress was also made in far-field and high-noise environments — allowing one to shout across a room to a device or whisper sweet nothings to your AirPods in the office.

Importantly, products like the Echo seem to have crossed some sort of “latency barrier,” — delivering responses quickly enough that mainstream users will engage, experiment and tolerate failed queries.

While many of these advancements begin in large company research labs, the emergence of full-featured authoring and runtime platforms like PullString and platform-provided tools like Amazon Lex are lowering the investment required to create conversational experiences. Components makers like Qualcomm are even pulling generic features like active noise canceling into their Bluetooth chips.

New Computing Nodes

Listening devices are everywhere this year; this explosion of nodes is driven by some major players’ moves, as well as entrepreneurial opportunism as the home IT budget comes up for expansion and refresh (pre-read: my partner Josh’s post from last week).

Apple’s headphone jack-free iPhone 7 was a hard shove in the direction of truly wireless accessories. Whether we judge this as a courageous move or just good ol’ Apple arrogance, they’ve shifted the market with this design choice and the launch of their AirPods. Alexa swiftly evolved from well-executed consumer speaker to voice control platform. Its subsequent adoption by a rapidly growing crowd of new hardware companies as well as established companies including Ford and BMW is driving developer-side experimentation and consumer awareness. Of course, upstart hardware makers are playing for a piece of the pie too: the soon-to-ship Here One and Nuheara earbuds promise us precise control of our audio environments, the Waverly team targets the Babelfish dream, the Kapture wants to lets you go back in time to hear anything again, and the Maven Co-Pilot aspires to keep drivers safe; and countless other well-funded Kickstarter audio hardware projects explore the boundaries of audio-centric helping.

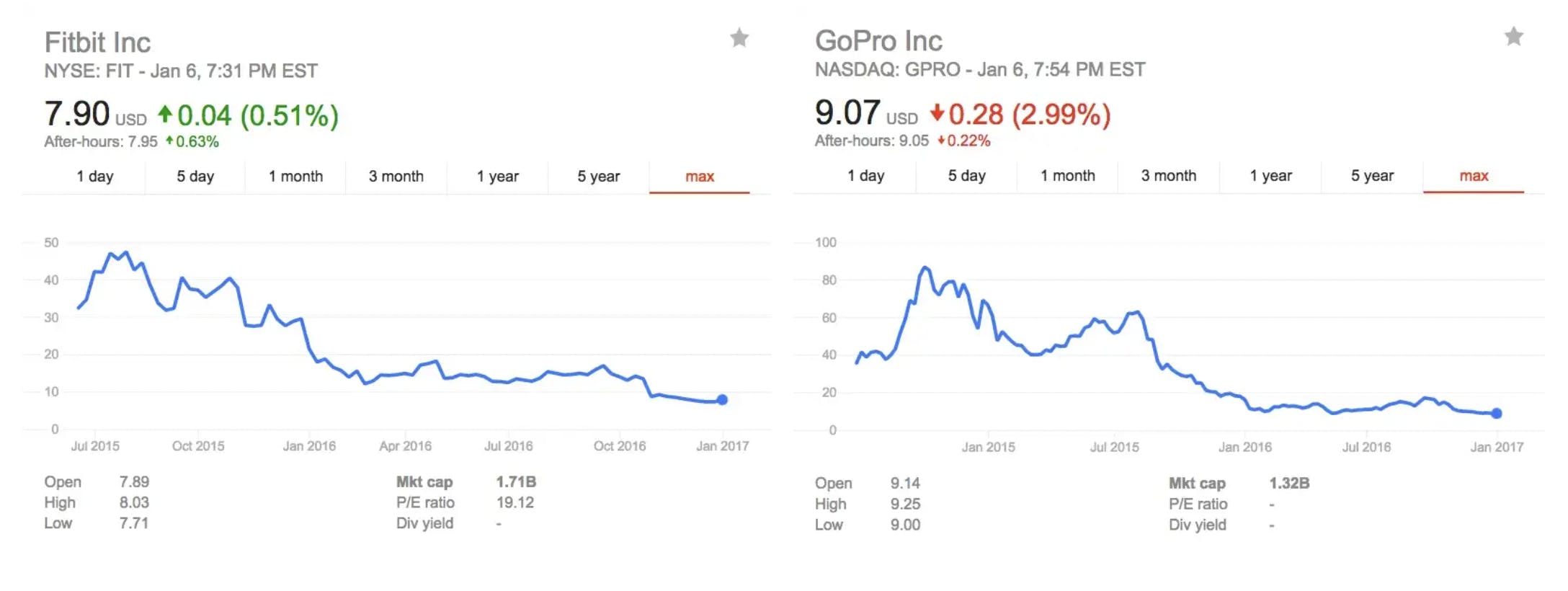

Demos are easy and hardware is hard (is there data available on the average ship date delay and NPS on delivered crowdfunded hardware projects?). Owning any kind of mass hardware footprint with on-device processing and an internet connection would be a valuable foothold for a startup — particularly if you can also build ongoing engagement. Hardware companies face a two-mountain path to success; even if one attains mainstream initial distribution, without rapid progress toward ongoing engagement, the markets will treat you brutally. Despite this, I’m excited by some of the impressive prototypes and products I’ve seen.

Many devices and applications would benefit from simple voice commands, stopping short of full-featured voice-centric design. It would be natural to make a presentation via Apple TV and say “next slide” instead than futzing with a clicker. How long until we get Snap Spectacles where we simply need to say, “Snap” to start recording?

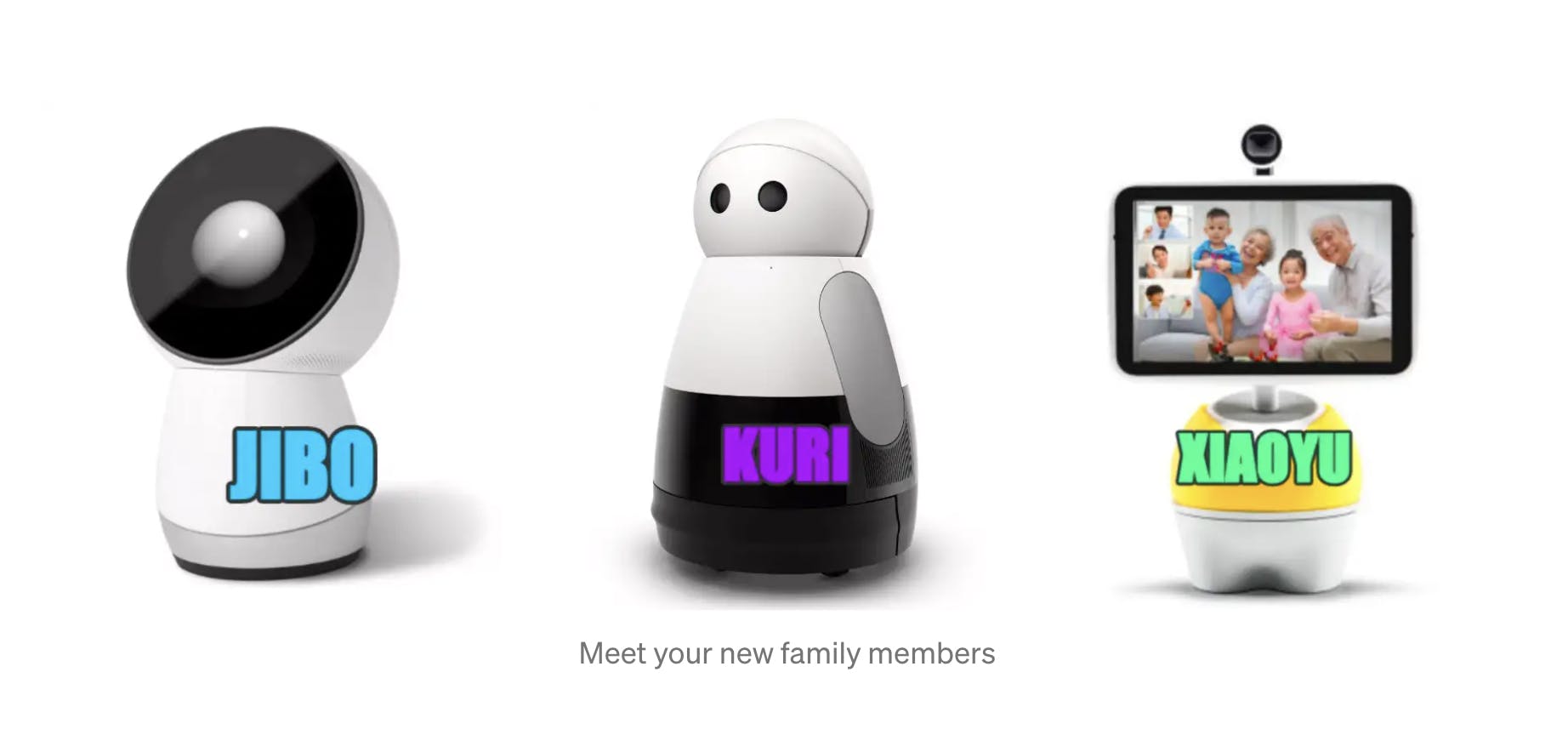

In contrast to these lightweight applications of voice, a potentially large opportunity for new voice-centric nodes is home robots — from the friendly desktop Jibo, to Mayfield Robotics’ BB8-like Kuri, to Baidu’s just-announced DuerOS-powered Little Fish. These family robots are intended to help coordinate between family members, take photos, entertain, and communicate with the outside world — for example by ordering food and groceries from a shared shopping list. Researchers are also looking at how the usability of voice assistants can be leveraged by the elderly. Mostly just launched or not yet shipping, 2017 will be a test for whether these friendly servants can find a market.

Companies are also building commercially oriented robots to interact with customers. One example is the humanoid SoftBank Pepper — coming soon to work in retail stores near you. Terrifyingly, semi-autonomous robots equipped with audio, facial-recognition and tasers robots are already being deployed for physical security. The commercial case for these kinds of robots is much simpler to make than that for home robots— they’re replacing human workers or improving the capacity of a store to serve customers or maintain security.

Voice-Native Applications

Software people are experimenting more with audio and voice on mobile, too.

I look to China for a lot of voice and messaging design inspiration. Perhaps driven by the difficulty of typing the language, the leapfrogging of desktops for mobile, or by the sheer ambient noise level of the country, voice input has long been not just culturally accepted, but dominant in China. Baidu’s talk-type keyboard is voice-first. We think SnapChat voice filters are oh-so-fun, but the Chinese had them in 2012 in WeChat. Papi Jiang, China’s biggest internet celebrity (which is saying something), only appears in her videos with an altered voice.

Companies like Oben are taking translation and speech synthesis to the next level, so you can speak another language (in your own voice) or play games voiced as yourself. Teams like Roger are iterating on the push-to-talk paradigm. Podcasting is a long-neglected category, choked by Apple’s progress-free native application. But in the Android ecosystem, new players like CastBox are emerging, and the talented people behind Bumpers are making it easier for the mainstream to create and share audio from your phone. Talkitt is trying to help the speech-disabled. On the B2B side, Cogito and BeyondVerbal do emotional analysis on voice for different use cases, for example understanding patient sentiment in a healthcare system. Nuance has long offered basic transcription applications to aid in medical charting, though there is still enormous progress to be made here. Gong and Clover Intelligence will analyze your sales reps’ phone calls.

Data Ingestion, Not Data Entry

Ask someone what they hate about their office job, and a pretty universal answer is data entry. With the adoption of business technology, we’ve created millions of hours of labor around mindless, modern-day paperwork — software-work. If we can record our conversations and make sense of them (extract structured data), we can remove these digital form-filling workflows. This will unburden many, from the technology sales representative that needs to summarize his customer interactions, to the doctor that today spends more time interacting with EPIC software than his patients.

Bao, Pierce, et al., 2011

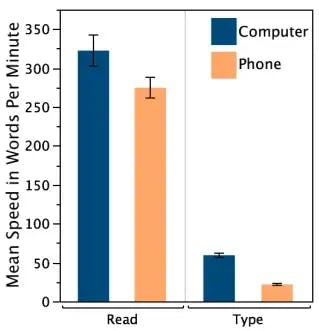

At a more mundane level, improving text input on mobile will expand the set of applications we use. Typing on mobile is objectively bad, even for the most mobile-native teen. According to one UC Santa Cruz study, on mobile we’re 2.7x slower WPM vs. typing on a desktop, and 6.4x slower vs. speaking (at 140–150 wpm).

This difference, combined with the pain of entering credentials, the limitations of small screens, and the fragmented attention engendered by smartphones means most users still avoid content creation and other input-heavy business tasks on mobile.

Can we enhance (eliminate?) note-taking? Do we want to? If each of us could have a private, high-quality scribe available at all times that not only remembered everything but made sense of it, for the cost of a software subscription, I’d wager yes. Especially if that meant we could focus more absorbing information, or being present with the people we’re interacting with.

As one peek into the future, at the Greylock Hackfest last year, one awesome team (Jenny Wang, Will Hang, Guy Blanc and Kevin Yang) worked on an ambitious project they called GreyLockscreen. Their project used always-on, ambient listening, natural language understanding (NLU), and deeplinking to predict and surface content and actions to a user from their smartphone, rather than requiring an explicit command. For example, if you had your phone on the table and you mentioned to your friend, “Jenny, I’m hungry, let’s get Sprig” an implementation of this might be to surface a pre-populated Sprig cart. Researchers are investigating related product concepts such as “ambient document retrieval.”

Challenges

NLU and Audio Processing

Voice suffers from nearly all the same technical issues that messaging bots do today, in addition to the requirement to transcribe accurately. Despite impressive recent advances in language understanding and speech synthesis, it’s still a formidable task to create a compelling voice-based experience and often involves new research.

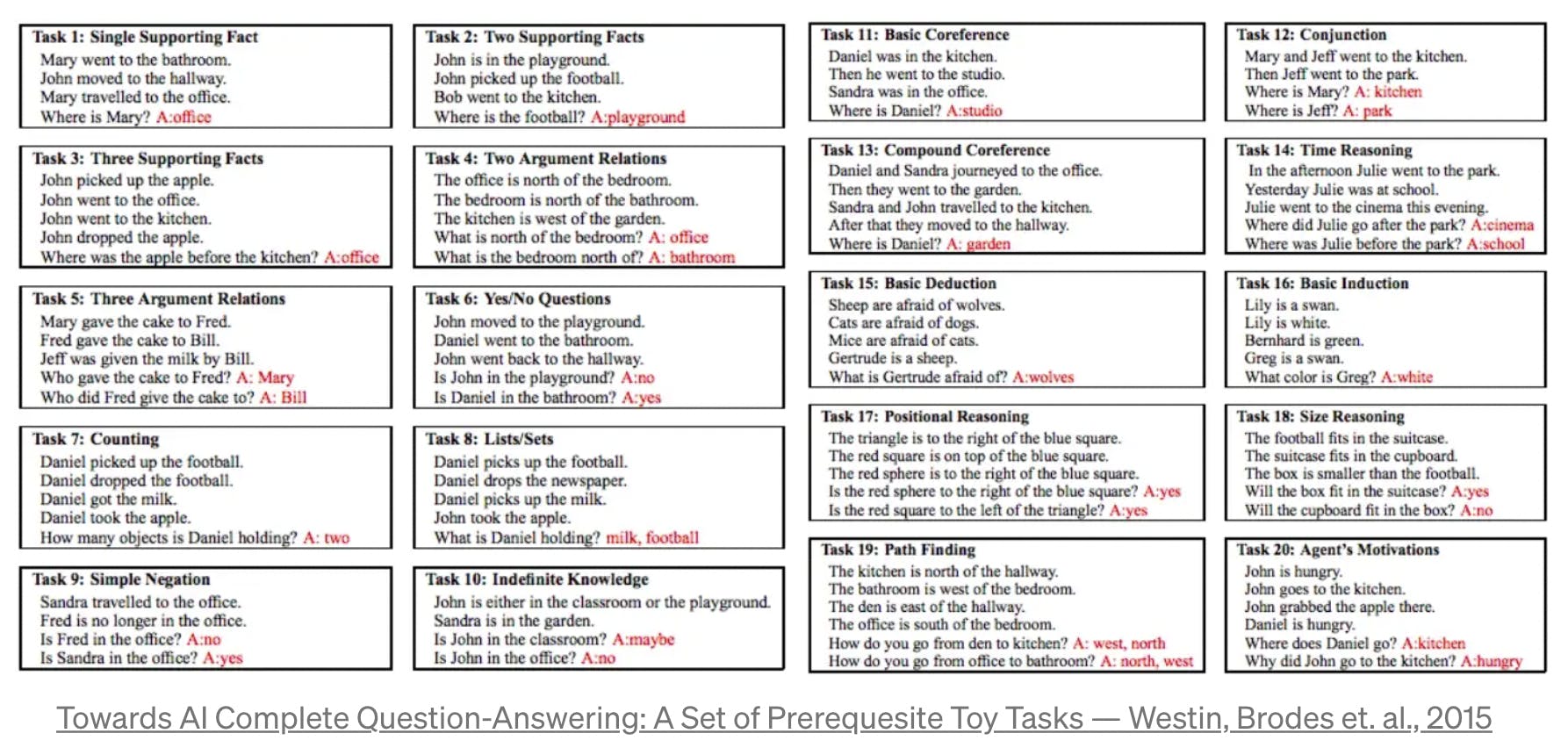

To vastly oversimplify and repeat myself a bit from an earlier blog post that covers technical challenges in NLU, deep learning has been remarkably successful at perception tasks — for example recognizing a word or labeling an image. NLU is a very difficult problem that begins to look similar to artificial general intelligence (AGI) — not just perception but cognition. Large labs like Facebook’s are actively researching these issues of reasoning, attention and memory. For example, answering questions based on facts, counting, creating lists, coreference (two expressions referring to the same thing), understanding time, inheritance of properties, size and positional reasoning are some of the reasoning tasks that Facebook has set out to tackle on a limited dataset. We have a very long way to go.

Smaller companies like Ozlo are bringing in the scope of the problem, starting narrow with a domain like food and places. But even in constrained problem space, one must make complex decisions. What reviews are trustworthy? Even if we can accomplish the kind of reasoning suggested by Facebook, we’ll just be scratching the surface of “knowledge.” Training data for natural language models will be by definition, user generated — and what is a fact?

In audio itself, there’s still plenty of work to be done beyond transcription — unsolved issues like accents, different environments, speaker recognition, and better, more emotional text-to-speech. For example, every sound that goes into a Google Assistant or Siri sentence is still painstakingly voiced by a voice actress, and then cut up and reassembled in a process called “concatenative speech synthesis.” This method is expensive, still sounds choppy, and is hard to add emotional color or emphasis to. However, here again deep and reinforcement learning seem to be making strides, for example with the recent WaveNet results from Google DeepMind, based on modeling the raw waveforms in audio.

Uncharted UX Territory

Because our technology is not yet where we want it to be, we need to smooth the edges over with good design. Today, not being understood by a voice-enabled machine, without recourse, is infuriating, and it happens all the time. How many times have you yelled at your Alexa? What percentage of the time do your assistants respond today, “I’m sorry, I can’t find the answer to that”?

Designing for voice interactions is still in its early days, and there are unlimited inputs to a flat interface. There are no natural limits to what users can say, and dangerously, they naturally attribute human characteristics to voice systems. In the next few years, voice systems simply will not be able to react to many queries correctly. Even without solving NLU problems, we can improve usability, and we will see expanded interest in voice interface design.

Supporting user control and freedom, improving flexibility and efficiency, preventing and handling errors, and perhaps even using shareable design will all help. Our voice assistants will be much better when we can teach them specific shortcut commands, names, defaults and hotwords, and when communal devices support unique user profiles.

Screens have massive relative information density, and multimodal voice+screen experiences will be the right short-term solution to many problems (see rumors about the Echo with a screen).

Necessary enabling tools for voice prototyping and analytics like Sayspring and VoiceLabs have already begun to emerge.

Compute Power and Battery

Some of the most common complaints with Siri are that it’s slow, can’t reach the Apple server farm and it doesn’t work offline. Actually, none of the current major voice assistants (Amazon, Apple, Google) work locally — their brains are all in the cloud back-ends of their respective parents, and this is unlikely to change anytime soon. Responding to voice queries requires sophisticated machine learning-based model inference, an intensely compute-heavy task.

Always-on listening and connectivity are power-hungry features. Thus, we see most voice controlled, wireless products require a button tap to engage, rather than a hotword: e.g. the portable Echo Tap, and making use of separate, specialized processors, such as the DMBD4 and the Apple W1.

Privacy, Security and Authentication

Suddenly, I’ve got no less than ten devices in my home that are always listening to me — Apple TV, Samsung TV, Xbox, Google Home, an Echo, two Dots, and our iPhones and AirPods.

Today, I’m unnerved by the surveillance of voice-activated devices, but in the same way I’m troubled by the richness of my browser and search history.

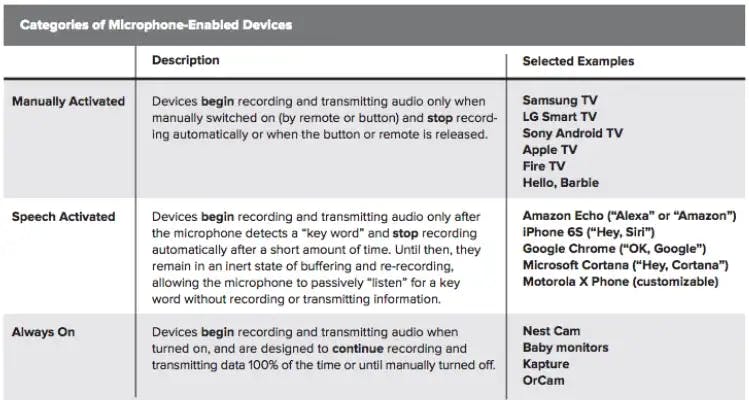

However, the Future Privacy Forum’s categorization of these devices is worth understanding. The only time these companies record and keep your voice is when you activate them.

Categories of Microphone-Enabled Devices

This would be very different in a world which recorded audio without a hotkey like “Alexa.” That could begin innocuously, with an expansion of the time window around the hotkey. What if Google recorded and sent the 90 seconds prior to any “Ok, Google” request, in order to collect more context and give you a better answer? Would you allow that?

Fears around mic’ed devices feel similar to those around the cameras that increasingly surround us — though at least security cameras tend to be pointed out of our homes, not inward. Even if we are comfortable with the intended features of internet-connected cameras and microphones, these devices may themselves be insecure, or they may be used for government surveillance. Can we guarantee against a backdoor into every Alexa Echo, and if not, what would it mean? Are you comfortable with strangers, friends and colleagues hearing your dictated commands, conversations, and thoughts if they’re in eavesdropping mode, or would you adopt the creepy-looking but inspired Hushme muzzle?

Finally, for us to access many important services through a voice interface, we must be able to authenticate into them. Alexa has purchasing from the associated Amazon account default-enabled, leading to ecommerce-capable children, office-pranking and a newscaster accidentally ordering his audience dollhouses. More seriously, if I want to access my Bank of America account through their virtual assistant Erica, how will she know I’m me? Traditional credentials seem like an even poorer solution on voice-based devices than they are on mobile. Some point to voice-as-biometric authentication as a more likely bet. Unfortunately, voice biometric solutions feel unsustainable as a solo solution. Just as photo manipulation software means seeing is no longer believing (somehow, every fifteen year-old on social media today is better looking than I was at that age), audio manipulation and synthesis technology suggests that very soon hearing will no longer be believing. And while today there are varied state-level rules around consent for voice recording, far-field microphones makes enforcement more difficult.

These interfaces are yet another push away from today’s flawed authentication methods toward behavioral, contextual, risk-based identity systems that take into account many different signals.

If I am within the geofenced zone that is my home, my Echo is on the same wireless network as my smartphone, my voice is a biometric match to the voiceprint Amazon has on file, and I’ve successfully passed Okta’s second-factor authentication, the odds I am me are much, much better than your average online banking login.

Dreaming of the Near Future

Today, it may seem as though we are struggling uphill to build a relatively narrow set of imperfect voice-enabled applications and devices, but we will see voice commands and assistants emerge everywhere. What we will want from our intelligent assistants will be governed by their level of intelligence, and our creative design around the gaps in that intelligence. This period of many new computing nodes and new ways to interact on mobile is a massive opportunity.

The technological and cultural barriers to useful conversational services feel at this point more surmountable than ever — and what lies beyond sparks the imagination, as research on subvocal communications and brain-computing interfaces sneaks out of the dark fringes into the twilight of possibility. Systems based on NLU and dialogue will be some of the most significant applications of modern machine learning over the next decade.

Are you building something cool with voice? I’m listening!